Walking the Talk: Indigenous Leadership Advances Inclusive Conservation Worldwide

Pastoralists are mobile people… but the project will open the eyes of our authorities, other stakeholders… to recognize their knowledge – preserve it and understand it.

— William Naimado, IMPACT – Kenya and ICI 2024-25 International Environmental Policy Fellow

In Northern Kenya, William Naimado and his IMPACT – Kenya colleagues pour over maps, surrounded by elders, women, and youth from their pastoralist communities. In hand are a series of maps – not merely of roads or borders, but of memories, ceremony, grazing routes, medicinal trees, and traditional meeting sites. These are maps that didn’t exist a year ago – and they might just help change the future of their communities.

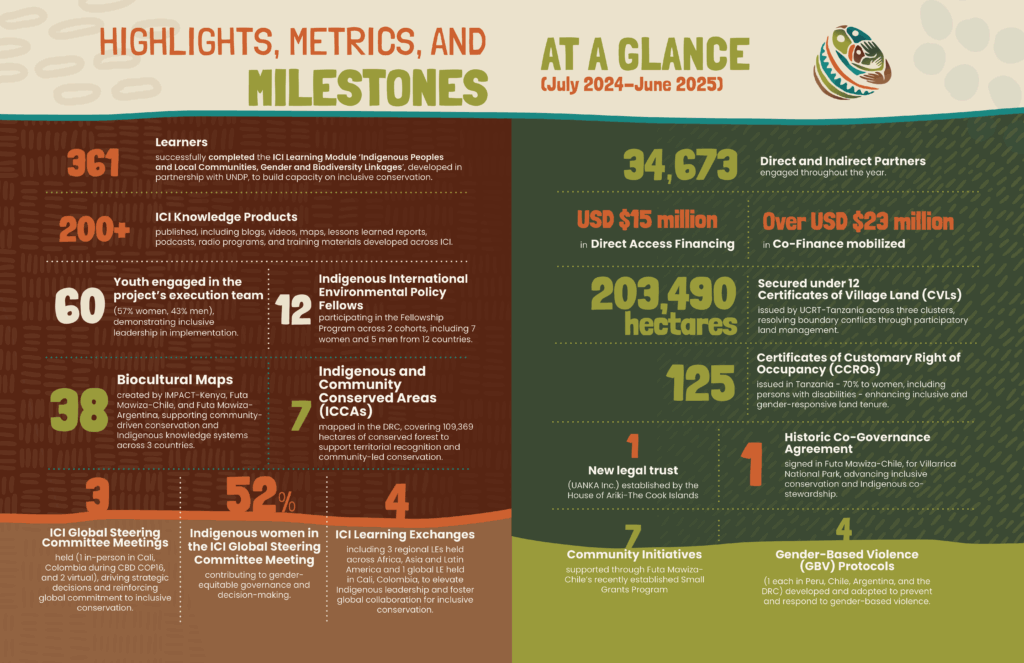

From July 2024 to June 2025, the Inclusive Conservation Initiative (ICI) entered a pivotal new phase. Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs) were directly implementing conservation strategies that they designed over the previous few years. Stretching across 10 territories in 12 countries, this third phase of ICI marked the first full year of on-the-ground action under Indigenous leadership. In doing so, it began to provide proof of concept for the power of inclusive conservation finance by centering on Indigenous governance and meaningful partnerships to accelerate progress.

Backed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and implemented in partnership with Conservation International (CI) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), ICI is not only offering a vision, but a roadmap for what truly inclusive and equitable conservation can achieve – by walking the talk together.

Indigenous leadership in motion

Over the past year, ICI partners rolled out dozens of locally led conservation efforts that span more than 6 million hectares of land and seascapes. Each of these efforts was led by IP and LC organizations themselves – some of whom are receiving and managing large-scale grants of up to $2 million USD for the very first time. This decentralization of funding marked a historic shift in conservation practice, enabling communities to steer their own priorities, timelines, and governance approaches at both global and local levels.

By the end of July 2025, all IPs and LCs-led projects had:

- Begun ICI-focused implementation of inclusive governance structures;

- Launched tailored training, mapping, and environmental monitoring activities, which have already begun to yield land tenure and security results; and

- Developed innovative mechanisms for stakeholder dialogue and national policy engagement.

IUCN, CI, and IP and LC partners also leveraged significant co-financing and built new alliances at national levels – demonstrating not just local leadership, but a growing systems-level influence.

A new model

A core achievement of ICI’s third phase was the transformation of how IP and LC organizations interact with conservation finance systems. Historically, rigid administrative systems created bottlenecks for local actors. ICI worked through numerous challenges to pilot and test ways to flip that script.

Through direct sub-grants to Indigenous organizations and adaptive technical assistance, partners improved their administrative and absorptive capacities. Importantly, ICI supported these shifts with tools that made monitoring and accountability more efficient and accessible – such as the ICI Project Hub (an internal virtual knowledge management system) and peer-led learning exchanges, which took place at global and regional levels.

As a result, partners are delivering high-quality reporting that better aligns with Indigenous rhythms and timelines – all while maintaining strong financial stewardship and advancing rights-based conservation outcomes. This past year’s work demonstrated that simpler systems, when paired with locally relevant support, lead to better results.

Centering Indigenous knowledge and worldviews

In all territories, conservation planning was grounded in biocultural values. From seed saving in northern Thailand to spiritual mapping in Kenya, communities documented the ways in which they apply Indigenous knowledge systems to environmental stewardship. These were symbolic acts – but strategies of resiliency.

The participatory mapping of cultural and ecological sites played a central role in defining conservation priorities and governance boundaries. In many cases, such maps have already been successfully used in land claims, resource management plans, and government dialogues. For example, in Tanzania, 125 Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy were issued to individuals while 12 Certificates of Village Land covering 203,490 hectares were issued – resolving boundary conflicts through participatory land management. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, 7 ICCA sites covering 109,369 hectares were mapped, supporting the recognition of Indigenous territorial rights and enhancing community-led conservation in the newly established Kivu to Kinshasa Green Corridor. In Kenya, 18 of 24 community lands engaged in ICI are now registered under Kenya’s Community Land Act – with three more currently in progress. In the Cook Islands, the House of Ariki established a formal trust (UANKA Inc.) to work alongside traditional community structures to manage ICI and future projects – reflecting traditional leadership values within a self-determined legal framework.

Across all sites, these efforts were intergenerational, gender-inclusive and responsive, and centered in Indigenous languages and worldviews. As William observes, “As much as it is building the communities, it is building us as young people, as young upcoming leaders.”

Indigenous women’s leadership

One of the most striking cross-cutting impacts of ICI’s first year of fieldwork was its role in advancing gender equality and Indigenous women’s leadership:

- All 10 territories developed and started implementing Gender Action Plans;

- More than 1,800 Indigenous women were directly engaged in women’s economic empowerment initiatives, land rights advocacy, and training programs;

- An Indigenous-produced e-module on IP and LC women and biodiversity was launched in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme – with 1,200 people currently enrolled, of whom 361 have completed the curriculum;

- In Tanzania, 9 Women’s Rights and Leadership Forums were formed or expanded;

- In Thailand, Indigenous women are being supported in documenting FPIC processes and preserving traditional knowledge systems essential for biodiversity and land use; and

- In Guatemala, 178 Q’eqchi’ women were engaged in cacao value chains while another 1,100 Indigenous women are receiving entrepreneurial training in agriculture and forestry value chains.

In Argentina, Chile, the DRC, and Peru, community-based protocols to prevent and respond to gender-based violence were designed and started implementation – laying the groundwork for long-term institutional change. These shifts were not only about inclusion, but about building more responsive, sustainable, and resilient conservation efforts.

What this year taught us

From East Africa to the Amazon Basin, and from the seascapes of Fiji to the ancestral lands of the Himalaya – ICI’s first full year of field implementation brought powerful insights that are already shaping the next phase of work.

- Trust and flexibility matter more than timelines – Conservation systems that prioritize rigid deadlines over local realities often fail or create unnecessary friction. ICI’s approach showed that building in flexibility, especially during procurement delays, political instability, or climate-related disruptions, yields more equitable and sustainable outcomes.

- Indigenous monitoring systems are strategic assets – From gender-responsive indicators to culturally grounded metrics, IP and LC monitoring systems offered not only stronger community ownership, but better data.

- Maps are most useful when they are personal first – Biocultural maps succeeded not because they were technical outputs, but because they were community-authored and community-owned – building bridges between Indigenous peoples and governments.

- Shared learning builds collective power – ICI’s learning exchanges – both peer-led and context-specific – offered a platform for IP and LC organizations to build collective voice and shared advocacy agendas. These spades also provided strategic support for navigating bureaucratic systems that are often exclusionary.

- Local leadership is the best investment – Whether it’s mapping sacred sites or navigating national policies, IP and LC partners demonstrated strategic leadership. The ICI experience demonstrates the impact of what happens when funders like the GEF support the creation of enabling environments – something ICI continues to refine through trial and practice.

- Leadership doesn’t wait for permission – With the support of their elders, young Indigenous leaders are emerging, equipped with new tools and grounded in their traditions, they are powerful advocates for their peoples and territories. In Mesoamerica, elders and youth have channeled the Mayan cosmovision and linked conservation practices into two diploma programs in Guatemala. In Fiji, traditional voyaging and navigation are being revitalized among youth. In Peru, 103 Indigenous youth are taking advantage of a media workshop to amplify their abilities to conduct advocacy.

Looking ahead – a call to scale what works

As the global community races to meet biodiversity targets, the lessons of ICI are clear: inclusive conservation is not only a moral imperative, it is an operational necessity. It leads to stronger institutions, more just outcomes, and deeper commitments to both people and planet.

But scale is not about replication, it’s about adaptation. The work that succeeded in the rangelands of Tanzania cannot be copied and pasted into the Pacific. Instead, what must be scaled are values: trust, equity, co-creation, and cultural continuity.

The first year of field implementation was a proof of possibility. With continued investment, aiming to increase large-scale funding to IP and LC organizations, streamlined systems, and bolder partnerships, the path forward becomes clearer. In fact, IUCN is expanding support to several ICI partners under its PODONG Indigenous Peoples Initiative, bringing additional large-scale finance to IP and LC organizations. CI has been leveraging its Dedicated Grant Mechanism project to increase knowledge exchanges among IP and LC partners from around the globe.

From recognition to redefinition

“For decades, we’ve acknowledged the role Indigenous Peoples play in protecting nature. But recognition alone doesn’t shift power. Walking the talk means restructuring how finance flows, how decisions are made, and who holds agency.

— Carlos Manuel Rodríguez, CEO and Chairperson, GEF

The past year moved mindsets. IP and LC organizations are no longer “emerging” players in conservation; they are central to its future. In this pivotal year, ICI partners walked together – across boundaries, across languages, across histories – and forged the path as they went.

This is a story of agency. And it is just the beginning. Now, the invitation is open – to governments, funders, and global allies – to walk this path together.

“Through ICI, our communities are not only being seen—we are being trusted. Trusted to lead, to make decisions, to manage resources, and to care for our territories in the ways we always have. This report does not just reflect a summary of activities. It reflects a shift—a shift in who holds the pen, who holds the funds, and who holds the knowledge.

— Vivian Silole (Ilaikipiak Maasai, Kenya) and Jorge Nahuel (Mapuche, Argentina), 2025 ICI Global Steering Committee Co-Chairs

Reflecting on the momentum thus far, without skipping a beat, William shares that, “The best part is how the communities are receiving it – embracing the Inclusive Conservation project – naming it and terming it as they understand it best… We really hope we don’t stop here.”

Click to read the full report.

Follow on Instagram @ipsleadnature

Engage on X @ipsleadnature